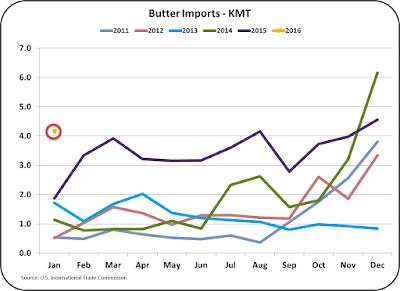

Decreased exports and increased imports are significantly reducing demand for U.S. produced dairy products. Cheese exports are down 8% in January, a six-year low, and cheese imports are at record levels for the month of January. Nonfat dry milk exports were up slightly for the month of January, but so were imports, resulting in lower net exports. Butter imports were also at a six-year high for January. When imports are up, some of the domestic demand for these dairy commodities is being satisfied with imports, reducing the demand for U.S. produced dairy commodities.

Cheese is always the most important dairy commodity for pricing producer milk. In January, cheese exports were are 2013 levels, a three year low for this month.

Cheese imports were above the prior five years by a significant amount. The sources of the imports are shown later in this post.

The result is that cheese net exports were below the last five years as shown below. The

prior post showed the impact on U.S. cheese inventories that continue to build. With larger inventories of this perishable product, prices will continue to decline.

Imports of cheese are coming from many countries, some new sources and some expanded sources. The largest new source is New Zealand, followed by Australia, Denmark, Ireland, and Nicaragua. Obviously U.S. cheese buyers are finding many sources of lower priced cheese on the international markets.

Cheese exports are down to all major importing countries except Mexico. The largest loss by far is South Korea.

As mentioned in the prior post, cheese production must be reduced to keep cheese inventories in line. If they are not, NASS cheese prices and the Class III milk price will continue to decline.

Butter imports continue to increase, up significantly for the month of January. This has kept the U.S. as a net importer of butter (imports are greater than exports.) Imports are currently 5% of total U.S. butter consumption.

Butter is being imported primarily from Mexico. U.S. produced butter is much higher priced than Mexican butter. Additional increased imports are likely.

Nonfat dry milk exports were up slightly in January, but so were imports. The net result is a four-year low in net exports of nonfat dry milk. The price is also very low, keeping Class IV milk prices very low. Nonfat dry milk is still the largest export dairy product for the U.S.

Exchange rates are one of the big culprits in making U.S. dairy products unattractively priced on the international markets. Below are the exchange rates between the U.S. and its major international dairy trading partners. Europe and New Zealand are major dairy exporting countries and Mexico is the U.S.'s largest dairy importing country.

Versus historical exchange rates, all show a 20% or more drop. This simply means that U.S. dairy commodities are 20% more expensive than previously based strictly on exchange rates. It is difficult to compete with this large a spread. The U.S. continues to recover well from the 2008/9 financial crisis while much of the rest of the world continues to struggle. A strong USD can be a point of pride, but it can also make exporting difficult.

CONCLUSION

International conditions are causing low U.S. exports and high imports of the dairy commodities, cheese, butter, nonfat dry milk, and dry sweet whey. In turn, they are forcing domestic prices lower for these commodities. Lower prices for these commodities result in lower producer milk prices. There is no short term reason to expect this situation to change. The most critical is cheese. Cheese production continues at a pace supported by a higher level of exports than currently exists. There is no clear sign that production of cheese will decrease. As long as these conditions continue, producer prices will not increase and may decrease further.