In July, butter prices were $2.32/lb. making butterfat worth $2.60/lb. The breakdown of the milk check was shown as coming 60% from butterfat and 37% from milk protein. However, if butter was at its longer term pricing of $1.50/lb., butterfat would be worth only $1.61/lb. With that change, milk protein would then be worth $2.95/lb. instead of the July price of $1.91/lb. The impact the Class III price would only change by $.40/cwt., but butterfat would contribute only 38% and milk protein would contribute 59%. The pie chart of component revenue would change drastically as shown below. (See these two prior posts for more detail on the analytical relationship between butterfat and milk protein pricing - August 7, 2016 and April 23, 2009.)

The current high butter prices have interrupted the long-term trends in the value of milk protein and butterfat. Butterfat is currently valued higher than milk protein. This has created a different point-of-view for dairy producers who now see milk fat as the primary revenue source. This runs contrary to the long-term diet trends which include more consumption of cheese (which requires higher protein levels) and lower consumption of high calorie fats.

Butter prices have remained above $2/lb. since 2013. This price is well above historic prices and well above international prices. At a time when milk prices are at extreme lows, how is possible that butter prices are at highs?

What are the factors keeping butter prices so high? There are at least three factors keeping butter inventories in check and prices high. They are 1) an increase in per capita consumption of butter, 2) reduced churning in the U.S., and 3) trade restraints on imports of butter.

Dating back to 1930, per capita consumption of butter was very high. However, during WW II, as alternate products were developed to compensate for the cost and availability of real butter, per capita consumption dropped dramatically. Over time, these butter "alternatives" improved and gained favor. Most of the alternatives were vegetable oil based and, included partially hydrogenated oils that were hydrogenated to attain a specific melting point. However, because partially hydrogenated oils contain trans fats, which are bad for heart health, vegetable oil spreads were changed to oil blends to achieve a specific melting point. During this change, butter gained favor based on concerns about partially hydrogenated oils and has since increased per capita consumption.

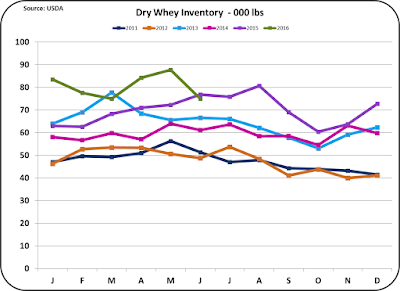

Churning of U.S. butter has remained stable. Because the U.S. population is up and individual consumption is up, there is not sufficient domestic butter available. Currently no capacity is being added.

The chart below compares European, Oceania, and U.S. wholesale butter prices. Obviously, for over a year, the U.S. price of butter has been well above the price of other major exporters in Oceania and Europe.

During this time imports have increased to 4 times the early 2014 level.

With the huge difference in the U.S. butter prices vs.international prices, the logical question is why has more butter not been imported. More imports would cause U.S. butter prices to more closely equalize with international prices. Supply changes certainly take time, but the change in imports happened quickly and has now leveled off.

A look at the sources can help explain this. We do have a free trade agreement with Mexico, which allows Mexico to ship butter (or the more concentrated form known as anhydrous milkfat) as long as its origin is Mexican. They cannot import butter and then ship it to the U.S. However, they can use imported butter for their domestic needs and ship more Mexican butter to the U.S. Mexico is our largest source of butter and for the first half of 2016, imports are up nearly 75%.

The other roadblock to additional imports is the two tiered tariff rate quota. Other countries that the U.S. has tariff rate quotas with can attain a license to export to the U.S. with minimal tariffs up to a certain level. Beyond that level, the tariffs are much steeper and in most case prohibitive. Over time, and with additional free trade agreements, the tariff and quota agreements will probably be lessened to allow more open markets.

The more immediate question is how long can the U.S. maintain the current price spread over other international suppliers. European butter is showing increases in pricing, but butter from Oceania is still well under $1.50/lb. In an age where free trade agreements are gaining favor, prices over time will come closer to equalizing. There is little doubt that this will happen, but the time schedule can vary with the politics of free trade and difficult negotiations with potential sources. The futures market is pricing these changes with butter prices falling to the low $2/lb. price range in 2017 and $1.80/lb. in 2018.

From a producer's point-of-view, while revenue today is primarily from butterfat, it is likely that this will change, and a producer should have plans to survive in a changing market which pays higher prices for milk protein and lower prices for butterfat.