Cheese exports were up slightly, but still below prior year levels. Butter exports continue their drop from a very low base, as U.S. butter prices are nearly twice international prices. NDM was up due to strong exports to Mexico, and dry whey continued its decline.

Imports were up across the board, helped by seasonal demand for butter and cheese and lower international prices for NDM and dry whey..

Exports to Mexico have been exceptionally strong, making up for some of the loses in other countries. As has been mentioned many times in prior posts, cheese exports which significantly influence cheese inventories, are the most important element for Class III milk prices.

Cheese exports while still down from the prior year, are up slightly from the prior month. Considering the difficult international market, this is a significant achievement.

If we look at the YTD shifts in cheese exports, only Mexico is up significantly. Mexico has become by far, our strongest export destination for cheese. While South Korea and Japan remain in second and third place, the loses have been huge. Cheaper sources, primarily from New Zealand, have cut deeply into overall exports of cheese.

A longer and more detailed view of importing countries shows the significance of these changes. South Korea was a major importer in early 2015, but that volume has decreased to less than half of the early 2015 volumes. Japan's imports have fallen from 2014 levels, but have been at a fairly consistent level since the beginning of 2015. Exports to Canada and Australia have been variable, but are consistent with past levels. The one country that is still trending lower is South Korea.

Mexico, our most important customer continues to increase purchases. The month-to-month consistency of current cheese exports in Mexico can be seen in the chart below. YTD exports are up 13%.

The prior post showed the increased level of U.S. cheese inventories as the volume of exports has diminished. Compensating for this has been a lower level of cheese production.

Who is the U.S. importing cheese from? The chart below shows imports by country. Imports from Italy and France are primarily branded specialty cheeses. Imports from the Netherlands and New Zealand are mostly bulk cheeses, which can be processed and packaged into retail or food service products in the U.S. The later bulk purchases are being commoditized.

Butter exports are nearly nonexistent. The Middle East has found less expensive sources and these butter importers have left their U.S. sources.

The U.S. is currently a net butter importer. The U.S. was a net butter importer from 2000 to 2008 beginning in 2009, exports flourished and imports shrunk. However, in 2015 the U.S. has again become a consistent net butter importer.

Where is the source of U.S. butter imports? The largest exporters of butter to the U.S. are shown below. Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, and France top the list. The imports from Mexico show the greatest year-to-year increase due to the NAFTA agreement.

Butter pricing in the U.S. has been called a bubble in many prior posts to this blog. The wholesale price of butter in the U.S. is approximately twice the international prices. U.S. per capita consumption is up, production is down, and imports are up. This market is due for an adjustment. Expect changes in 2016.

October was an excellent month for NDM exports. Export volumes reached near record levels for the month of October.

Who did the U.S. export all this NDM to? The largest NDM customer, was of course Mexico. More than 50% of the NDM exports went to Mexico. Exports to nearly all other countries were down from the prior year as international NDM prices from other countries are lower than U.S. prices.

Dry Whey exports were down 34% from the prior year. This is weighing heavily on inventories and dry whey pricing. Dry whey prices are the basis for "Other Solids" prices in the Federal Milk Marketing Orders paid on components.

This has resulted in "Other Solids" having a near zero value. Prospects for change are very difficult to determine and will probably not occur for some time.

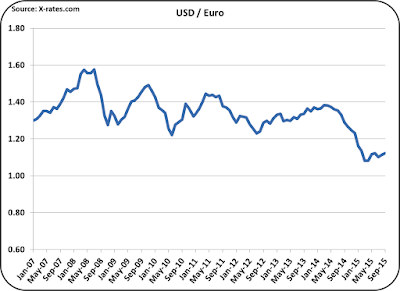

2015 has been a difficult year for dairy prices. The Russian embargo on dairy products was renewed and has hurt Europe's dairy exports. At the same time production quotas for milk production were dropped in EU and production surged, especially in France. China reduced imports of dairy products and left New Zealand with excess product. These excesses will be slow to normalize. The year of 2016 should be a year of recovery, but the recovery may be slow.