The U.S. dollar's value leveled off versus other currencies in the last few months. A weaker dollar improves cheese exports and reduces cheese imports.

The New Zealand Dollar that was strengthening in the first three quarters of 2009 has leveled off and even weakened a little in the last two months. A weaker New Zealand Dollar makes New Zealand cheese cheaper on the global markets.

As a result, cheese imports have leveled off. They are below the highs at the beginning of 2009, but are only slightly above the 2008 levels.

Cheese exports have also leveled off. They are not near the highs reached in 2008, but they have moved off the lows from early 2009.

In the November 19 post the correlation between cheese prices and U.S. per capita consumption was established. In late 2008, after many months of $20/cwt milk prices, cheese prices established new highs, reducing consumer consumption. Those cheese prices have now fallen to the historical trend prices and consumption can be expected to increase.

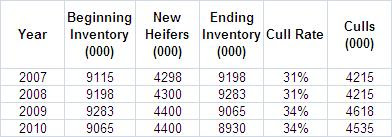

The USDA outlook for milk cows continues to forecast a very significant decrease in inventory. By the third quarter of 2010, the inventory is expected to drop to 8,950,000 cows.

A new report on cheese inventories is expected next week. Cheese inventories have been very high and must be reduced before a real recovery in cheese prices can be sustained.

If the pricing formula changes were evaluated at September 2009 Class III component prices, it would make a significant change in what the dairyman receives.

If the pricing formula changes were evaluated at September 2009 Class III component prices, it would make a significant change in what the dairyman receives.