Negative Producer Price Differentials (PPDs) are killing producer income. What is a PPD and what is its purpose? This post will examine why PPDs are negative and what it will take to make them positive. Some examples in this post will use data from three of the largest Federal Milk Marketing Orders (FMMOs), California, the Upper Midwest, and the Northeast, to illustrate the pricing impact of the PPD. The factors involved in a negative PPD are complex, and the explanation below is therefore a bit longer than most posts to this blog.

The current payment system for producer milk was implemented in the year 2000. It kept many of the legacy policies from the past. At that time, dairy was all about fluid milk. Today it is primarily about cheese. The payment system implemented in 2000 embraced the philosophy that fluid milk must be paid a premium to make sure it moves from the rural farms to the big cities where there are no cows. Fifty years ago, every major city had a processing plant to pasteurize and bottle milk. Today, that picture has changed. When Walmart built their new processing plant for fluid milk in Fort Wayne, Indiana, it was designed to process milk for 500 Walmart stores in the geographical area of Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio and Kentucky.

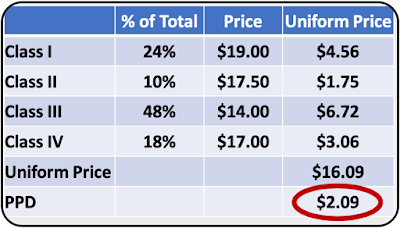

The PPD was designed to level the playing field for all milk producers to see that they were paid uniformly regardless of the end use of the milk. Under the Class and Component system, processors first pay producers for the components in their milk based on Class III formulas for butterfat, milk protein, and other solids. As complete data for the month is available, a weighted average or "Uniform" price of the all four classes is calculated. Because Class I is paid higher, that typically keeps the average or "Uniform" price higher than the payment based on components. The difference between the initial payment and the "Uniform" price is the PPD.

Chart I illustrates the progression of the PPD for the three biggest FMMOs. The three are quite different. California has a lot of low-priced Class IV milk in their mix, the Upper Midwest is all about cheese and Class III, and the Northeast has a fairly even distribution of milk in all Classes.

California has had a negative PPD for 12 of the last 13 months. The Upper Midwest typically has a very small PPD as most all their milk is Class III milk for cheese so the average or "Uniform" price is very close to the Class III price. The Northeast has provided producers with a positive PPD most of the time until the impact of COVID-19.

|

Chart I - PPDs for California, Upper Midwest and the Northeast FMMOs

|

There are five situations than can make a PPD negative:- An escalating cheese price which has been the major cause of negative PPDs in the past.

- A mix of milk Classes with a lot of the lowest paid milk, Class IV milk, can lower the "Uniform" price. (See Table I in the prior post for data illustrating this.)

- The new formula for Class I milk implemented in May 2019 has changed the dynamics of Class I pricing. Under the current circumstances of a high Class III price and a low Class IV price, based on the new formula, a negative PPD is likely. This did not happen with the old Class I formula

- A significant amount of Class III is being de-pooled. That increases the amount of a negative PPD.

- As less fluid milk is consumed, there is a smaller percentage of Class I milk. Because Class I pricing is formulated to be the highest paid milk, when there is a smaller percentage, the "Uniform" or average price will be lower.

1. ESCALATING CHEESE PRICES

First, the impact of an escalating cheese price will be examined. High Class I milk prices are intended to keep the "Uniform" price above the Class III price. Class I milk is priced by the Advanced system. The name sounds like it is a forward-looking price, but the opposite is the case. It is called Advanced but the price is determined for milk that has not yet been produced and is based on historical data. It is announced in advance of milk production and hence it is called the Advanced system.

The time line for pricing producer milk is shown in the graphic below for the month of October 2020. The Advanced Class I price is based on two weeks of data for September 11 and 18 and announced on September 22, 2020. Skim Class II milk is also priced in the Advanced system. The Class and Component pricing for all other Classes of milk is based only after the month's production of milk has been delivered to the processors. The Class and Component price for October was announced on November 4, 2020, six weeks later than the October prices for Class I milk and Class II Skim milk were determined.

|

Graphic I - Timing of Advanced vs. Class and Component Pricing

|

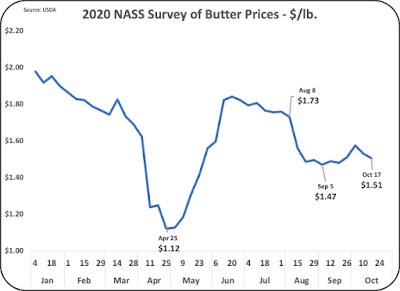

During the month of October, as the price of cheese increased, the Class I milk was based on a lower priced cheese than that used for Class III priced by the Class and Component system. The cheese price is the most important variable used to calculate the Class III price and the Advanced Class III price is part of the Class I price basis. The Cheese price used to calculate the October Class I price of milk was $1.75 per pound. The cheese price used for Class III milk announced six weeks later was $2.29 per pound. The escalating cheese prices set up a situation where the Class III milk price is higher than the Class I price. In that case, the "Uniform" price will likely be lower than the Class III price causing a negative PPD. Chart IV below shows how the Class and Component cheese price leads the Advanced cheese price by about six weeks.

|

Chart III - Cheese Prices for the Advanced and Class and Component pricing.

|

The impact of an escalating cheese price became a smaller factor in PPDs after the change in the formula for Class III pricing. More on that later in this post.

2. IMPACT OF A LARGE SECTOR OF LOW-PRICED MILK

The mix of Classes produced can also have a big impact on a positive or negative PPD. California and the Upper Midwest are at very opposite ends of this situation.

As covered in the prior post, in 2019 California had 40 percent of their pooled milk going to Class IV milk. In October 2020, Class IV milk made up 61 percent of the FMMO pooled milk in California. California also has a low percentage of the higher priced Class I milk. In 2019 California had just 22 percent of their milk in Class I compared to the average of the Federal Orders which had 28 percent Class I in their mix.

Class IV skim milk price is based entirely on Nonfat Dry Milk price which have traded in a tight and low-price range for 2019 and 2020 averaging around $1.00 per pound.

|

Chart IV - NDM Prices

|

The futures prices for NDM are expected to increase to around $1.10 in 2021. At $1.10 per pound for NDM, Class IV skim would be worth $8.30 per cwt. By comparison, Class III skim is currently running around $16.00 per cwt. A lot of the higher priced Class III milk in California and other FMMOs is being de-pooled, and therefore are not included in the "Uniform" price. Because the Class IV skim price is based strictly on the price of NDM, and influences the Class I price which is half based on the price of NDM, there is little hope for a positive PPD in the coming year in California.

3. FORMULA CHANGE FOR CLASS I

The Formula change for Class I did make a difference. See the

October 11, 2020 post to this blog for details on the formula change. Two charts have been updated from that post and are shown below as Charts V and VI.

The change in formula was implemented in May, 2019. Chart V shows the difference between the two formulas going back in history to the beginning of 2012. Until late in 2019, the change seemed to have a minimal impact on the Class I price. However, when the COVID-19 hit, things went astray. The impact of a high cheese price and therefore a high skim Class III price vs. a steady price for NDM and the skim Class IV price caused a major drop in the Class I price.

|

Chart V - Impact of Formula Change for Class I

|

The "normal" spread between the Class III and Class IV price is the basis for having a $.74 adjustment in the new Class I formula. Chart VI shows what happened to the spread between the Class III and the Class IV prices in 2020. The spread went as high as $10.96 per cwt. in August 2020. It remains high.

For the new formula to mimic the old formula, the spread between Class III and Class IV should average $1.48. As explained above, the Class IV milk price will probably remain within in a limited range. Therefore, the only way for the new formula to mimic the old formula under current conditions, is to drop the cheese price and therefore the Class III price. This would lower producer milk prices.

|

Chart VI - Spread between the Advanced Skim Price of Class III and Class IV prices

|

If NDM increased to $1.10 as now predicted by CME future data for 2021, skim Class IV would go to $8.30 per cwt. To match the intent of the new formula, then the Class III price would have to drop from its current level of $15.58 to $9.78 per cwt. Class III milk is the biggest category of milk and dropping by almost $6 per cwt. would negatively impact the price paid to producers.

4. DE-POOLING

When higher priced Class III milk is de-pooled, it increases the amount of a negative PPD. When there are fewer producers with high priced Class III, the Uniform price will drop and the PPD will decrease and/or become more negative. FMMOs like California and the Upper Midwest have seen a huge amount of Class III milk de-pooled. In California, nearly 100 percent of the Class III milk is currently being de-pooled. In the Upper Midwest, as much as 80 percent of the Class III milk is being de-pooled.

5. THE IMPACT OF LESS CLASS I BEVERAGE MILK

Cheese consumption is growing and fluid milk consumption is declining. As there is less Class I in the mix, the Uniform price will be lower. In turn, that reduces the PPD.

HOW LONG WILL NEGATIVE PPDs CONTINUE?

For now, to reduce or eliminate negative PPDs, cheese prices would have to drop drastically. While the FMMO cheese price will likely decrease some from current record high levels, it will probably not be a drastic drop.

In an earlier post to this blog, it was suggested that only the Class III price be used to calculate the Class I price. To match the old formula there would still have to a positive adjustment to make up for the infrequent times that the Class IV is higher than the Class III.

The way the formulas are calculated, currently the price of NDM determines the skim Class IV and Class II milk prices. Class IV milk determines the Class I price when averaged with the Class III price. In total, the price of NDM which is determined by international supply and demand and currency exchange rates, now influences 59 percent of the price of U.S. milk. By comparison, the value of dairy exports makes up only 13 percent of milk production. The low price of NDM may keep the PPDs low or negative for some time.

The PPD is the same for all pooled milk in each Federal Order but different between Orders. It is not under the control of a producer. But the higher components, as covered in the prior post, are under the control of the producer and will increase revenue and cash flow.