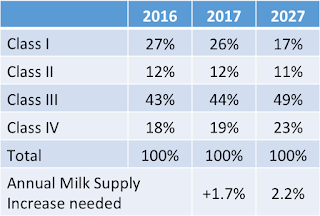

Chart I below shows milk usage by Class for 2016. To make a reasonably comprehensive chart of milk usage for the U.S., it requires not only the data available from the FMMO database, but also data from California expressed in FMMO terms. And finally, some estimates of the milk usage in FMMO areas must be added to include the milk that is de-pooled. Class I milk cannot be de-pooled, so the de-pooled amounts only exist for Class II, III, and IV.

If one makes the above adjustments, milk usage in 2016 looks like the following when expressed by milk class.

|

| Chart I - Milk Usage by Class - 2016 |

|

| Table I -Historic Growth Rates |

Beverage milk is falling, and therefore Class I milk will fall. It appears that the decline in consumption of Class I milk is accelerating. Cheese consumption has been growing and continues to grow, so Class III milk will continue to grow. The growth rate of cheese consumption is not plateauing but accelerating. Class III milk can be expected to increase with the increase in cheese consumption. Butter has turned around from its half century decline and is being consumed by more people in greater amounts. The growth rate of domestic butter, like cheese, is actually accelerating. To provide this butter, additional Class IV milk is needed. With the butter removed and the skimmed milk dried, additional nonfat dry milk/skimmed milk powder will have to be exported. There is always an international market for nonfat dry milk/skimmed milk powder if the price is right.

The last row in Table I shows the historic growth rate of the milk supply. Based on the trends in sales, what is this the appropriate rate of increase for the future?

To estimate the future need for producer milk, reasonable judgements of the historic data and some assumptions on the growth of exports, were used. Based on these, the growth rates in Table II below were chosen to estimate the future class milk usage and provide an estimate of the needed growth rate of the milk supply.

Class I milk is almost all domestic and is expected to continue it's decline by 2% per year. Because almost no Class I milk is exported, this rate of decline will be used for the entire Class I volume.

Class II milk, the smallest of the four categories, is shown to increase only by the population increase. The category is fairly stagnant, and the growth in yogurt has plateaued. Exports are expected to follow this same path.

Class III milk is the largest class and after years of 2% annual growth, the last two years have shown growth of 3.5%. Exports were growing by double digits until the last two years when exports declined. Exports are currently about 5% of cheese production. Exports would have to grow or shrink tremendously to influence the total and the new domestic high might not last. Therefore, a growth rate of 3.3% was chosen.

Class IV is forecast to grow by 4% per year. This is less than the current growth rate of butter consumption, but more than the historic growth rates. If Class IV grows at 4% per year, there will be a lot of nonfat dry milk/skimmed milk powder to export. However, except by importing more butter, the only solution is to make enough butter to meet domestic consumer demand.

|

| Table II - Class Growth Rates for Future |

Class III milk will grow to almost half of the milk produced. If the growth rate used is too aggressive, the growth to 50% will only be delayed, not capped. Class IV shows a huge increase from 18% of the milk produced to 23% of the milk produced. The big question is where will the remaining skimmed milk go. Some will go to spike protein for cheese making, but a lot more will have to be exported. At what price can this amount of skimmed milk be sold?

|

| Table III - Projections of Milk Classes |

|

| Chart II - Milk Usage by Class - 2017 |

|

| Chart III - Milk Usage by Class - 2027 |

And finally, what does this mean to the demand for producer milk? In 2017, it would indicate a need for an increase of 1.7% in the milk supply. This is roughly in line with the historic increases, but a little below some of the projections for 2017.

The really exciting part comes later as the beverage milk category shrinks in size. By 2027, Class I would be small enough that the continued decline would have little impact on the total need for milk. The total milk supply needed is dominated by the growth of Class III and Class IV milk. IF all these pieces came together in some fashion close to the projections in this model, the annual increase needed for the milk supply in 2027 would be 2.2%, far above historical levels.

The type of milk needed in ten years will also be very different. Processors would primarily need milk components. Cheese makers especially need milk protein and the increasing consumption of butter requires more butterfat.

You comments are welcome. Future projections have no right or wrong answers.