As prices for milk fall (see the prior post) and feed and labor costs continue to increase, what can producers do to increase revenue to stay in business and prosper? Higher component levels will certainly help. As shown in Chart I, component levels have been rising quickly over the last two years. What is covered here is not new or in any way confidential. What makes higher component levels possible? A mixture of genetics, cross breeds, diet formulations, management, and more.

Thomas Overton, PhD at Cornell University recently addressed the financial importance of improving components. His presentation was titled "Ways to Fatten up the Milk Check." The technology and ability to improve revenue with higher component levels is a regular topic in conferences.

|

| Chart I - Butterfat and Protein Component Levels |

Table I below shows the economic impact achieved in 2021 in the U.S. These numbers are based on U.S. averages. In 2021, increased component levels for butterfat and milk protein, increased producer revenue by $623,000,000. That is just the 2021 increase which will continue, and future years will build on this. All producers are paid for butterfat, but those paid on the Advanced system are not paid specifically for protein. The data in the table is based on 2021 prices for butterfat and protein. In 2022, with higher butterfat and protein prices, higher component levels will result in larger financial gains.

To put this on a more personal basis, the third column puts the money in terms of increased revenue per 1000 cows. The 2021 increase is worth $69,000 for every 1000 cows at 2021 prices. That is not a one-time increase, but a lasting increase to build on.

|

Table I - Increased Revenue from

|

Certainly, there are variations in the gains in component levels. Every herd is different, and some have seen results well above those in Charts II and III below. Obviously, some Federal Orders and some producers are further ahead in increasing component levels than others.

As of March 2022, butterfat (Chart II) in the highest Federal Order (the Northwest Order) is .21 percent higher than the lowest (the California Order). It is interesting that the highest and the lowest are both on the West coast. And, within each Federal Order some producers are well ahead of others. There is opportunity.

|

Chart II - Butterfat Component Levels for FMMOs

paid on the Class and Component system. |

There is a similar relationship with milk protein (Chart III). The Southwest Order is .19 percent higher than the Northeast Order. Again, there is opportunity.

|

Chart III - Protein Component Levels for FMMOs

paid on the Class and Component system. |

There is one other revenue generating opportunity. It applies to only four of the Federal Orders, but it can generate additional revenue. When Somatic Cell Counts (SCCs) decrease below 350,000 cells per milliliter, there is a bonus payment included in producer revenue. As shown in Chart IV, there have been recent improvements in the Southwest and Central Orders, raising producer revenue.

|

| Chart IV - Somatic Cell Count for four Federal Orders |

However, there is one revenue generating parameter that is not growing (Chart V). The slow down started in mid 2021 and has continued with no significant growth in milk pounds per cow. The growth in pounds of milk per cow have been growing for a very long time. Perhaps the current slow down is because of challenges to reduce feed cost, but considering the loss in revenue, that may not be advantageous.

|

| Chart V - Milk Pounds per cow per day |

The technologies for increasing butterfat and protein levels in milk have been implemented by many producers nationwide. Others can benefit by these proven technologies. The shifting economics and technologies of the dairy industry must be implemented if one is to stay financially sound in the coming years.

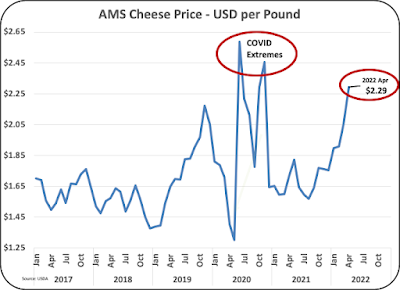

One technology that is typically used to increase component levels is amino acid balancing in dairy cow diets. Research indicates a typical increase of .18 percent butterfat, a .14 percent increase in milk protein, and a two-pound increase in milk production. At the April 2022 prices for butterfat ($3.15 per pound) and protein ($3.42 per pound), those increases would be worth $485,000 per year for a herd of 1000 cows producing 80 pounds of milk per day per cow. Because there is typically an increase in feed costs with amino acid balancing, the net income would lower. With the typical increase in feed costs, the net income would be closer to $448,000 per year.